Agreeing To Disagree Productively

The phrase ‘a good argument’ seems like an oxymoron. In fact, all children are taught from a very young age that arguments are not good and that it is best to avoid disagreements.

‘Why Are We Yelling?’ (2019) by Buster Benson provides a different view on arguments. Benson goes on to destigmatize the concept of arguing, stating that not all arguments are bad. He stresses the fact that arguments, only if unproductive, are detrimental, and that arguments can actually help improve personal relationships, broaden one’s outlook, and even help in performing better professionally. He encourages engaging in arguments as they can be crucial to opening up communication pathways and that they are a red flag indicating that something one cares deeply about is at stake.

He emphasises that arguments should be respectful and open. He also shows how being open to arguments and disagreements can bring out a positive change in people, making them not only less irritated with disagreements but also make them more perceptive to others perspectives.

Accepting Anxieties

In March 2019 the Internet lost its collective mind when it started bashing a Twitter user @alekkrautman for uploading a picture of a bagel sliced vertically rather than the traditional horizontal manner. Replies to the post reached a frenzy with people even stating, “Who told you this was okay?” and “First of all, how dare you”.

The question that arises is, what provoked an extreme response to such a simple matter? The correct way of slicing a bagel is a low-stake, light-hearted argument. However, it created heaps of anxiety among Twitter users.

One experiences anxiety when a valuable perspective is challenged and conflicts with a different viewpoint. Whether the stakes are low or high, anxiety is the basis of disagreements and is an unpleasant emotion. Hence it is humanly natural to experience angst, inciting dismissal and even downright attack.

Refusal of thoughtful engagement with matters that trigger anxiety can close the doors for any possible dialogue, growth, and even understanding, denying productive disagreement any opportunity to present itself.

Anxiety is individually unique. It is a complicated emotion that arises from a number of sources. For instance, two people disagreeing with each other could attach completely different anxieties to the same argument. Therefore, it is vital to categorize anxieties.

- Anxieties of the head, which are related to rational thought and information.

- Anxieties of the heart, which are related to emotions, and,

- Anxieties of the hands, which are related to practicality and usefulness.

In a situation where parents of a 12-year-old, leaving for an adults-only party, are left in the lurch by their babysitter cancelling out last minute, one parent opines that its unsafe to leave the child alone at home, while the other argues that it is perfectly safe and legal to leave a 12-year-old alone at home. Here we can see that anxieties of the head and the heart are at odds, and the argument between the two can’t be resolved.

Hence with anxieties, it is better to productively disagree by creating awareness of one’s own anxieties, triggers, and understanding the source of an opponent’s anxieties by exercising empathy.

Hear Your Thoughts

Hot-button topics such as gun control, vaccinations, and climate change ruled the roost in 2019. Additionally, these topics seemed extremely polarized with a middle ground in short supply. One can place the blame on cognitive dissonance.

When one’s own perspective is contradicted by another belief or behaviour, it results in cognitive dissonance. The more gaps there are between 2 different perspectives or behaviours, the greater is the anxiety and cognitive dissonance. Thoughts and voices in one’s own head then try to assuage the anxiety felt. These voices can be categorized into 4 types.

Let’s consider the polarized debate surrounding vaccinations to understand these voices. Two people, for and against vaccinations, are at a headlock in an argument. While one opines that vaccinations should be made mandatory for public welfare, the other disagrees that parents should be given a choice to vaccinate or not. Their diametrically opposing views cause dissonance and thus anxiety.

- Voice of power: The voice of power in both the opponents will want to shut down the argument completely and win the argument. The voice simply rejects the other opinion and doesn’t accept any other viewpoint.

- Voice of reason: The voice of reason uses evidence and reasoning to win the argument. It even calls out the opponent to prove their point with proof, evidence, and reasoning. It has a ‘Bet you can’t prove and win it’ attitude.

- Voice of avoidance: This voice simply chooses to stay away from the argument and steer clear from any discussion that challenges belief.

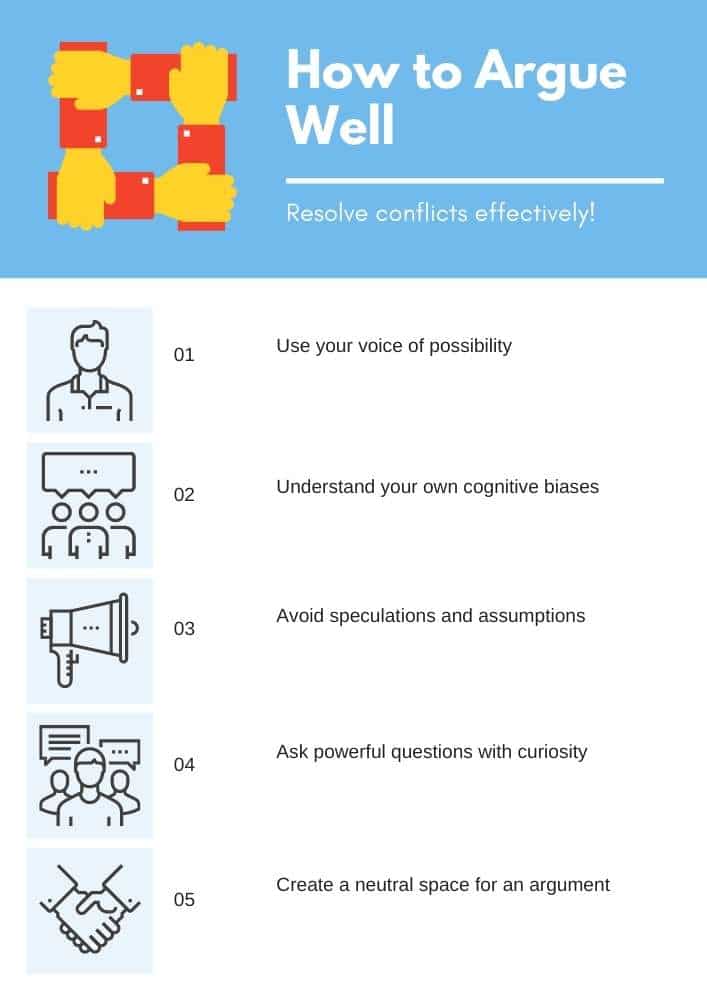

- Voice of possibility: Here, the voice is open to dialogue. It views disagreements as an opportunity to understand a different perspective.

Out of the four types, the voice of possibility is ideally the best way out. It is open to understanding a different view and has the potential to make space for it. Nevertheless, it doesn’t mean that while using the voice of possibility, one has to accept another viewpoint or change one’s stance. It is simply more receptive to another perspective.

One should thus, listen, know, and understand the voices in one’s own head.

Facing Biases

Let’s understand how biases work. In a choice between a chocolate gelato and a pistachio flavoured one, a person who opts for the chocolate flavour has done so simply because they do not like the flavour of pistachio. Never having liked the pistachio flavour, the bias against the flavour helped in making a useful decision. Thus not all biases are bad. They help in sorting the enormous amounts of information directed at us.

However, biases can have negative consequences as well.

Daniel Kahneman used the term availability heuristic to describe the bias that is manifested as a mental shortcut. This bias dictates that when faced with a decision, a person only considers those options that first come to mind. Availability heuristics are individually unique and hence, any solution or strategy that seems easy for one could be difficult, or even downright dangerous to another. The problem arises when two availability heuristics clash.

In-group favouritism is another negative outcome of bias. Those who are considered ‘part of our group’ are often given the benefit of doubt. Such biases can become extremely toxic, especially in high-stake disagreements such as politically inclined arguments. People tend to then dismiss the views of those outside the group.

Such biases, while can result in saving time and energy in the right context, can make one’s worldview limited, and restrict one from engaging in productive disagreements.

Unfortunately, cognitive biases do not have a switch-on-off button. One has to proactively and honestly acknowledge one’s own bias. Moreover, one has to openly admit that their own biases can limit the objective viewing of others opinions. One has to truly be self-aware that their own biases aren’t getting the better of them.

Avoid Speculations

How a person understands one’s own perspective during an argument or a disagreement and inhabits it can be one’s strong point. On the other hand, making speculations about an opponent’s perspective can be a weakness. It is human nature to speculate, oversimplify, or even demonize an opponent’s view while trying to comprehend their perspective.

Let’s consider a hypothetical situation. Two friends, Sofia and Bob, have had an argument over the 2016 elections. While it was one of the most closely won and contentious elections of all time, many chose not to vote. Sofia, when she found that her friend Bob was one of those who chose not to vote, was quite angry.

Why? Sofia’s reasons for voting for her candidate were very clear. She believed passionately in the candidate and she presumed that knew exactly why Bob hadn’t voted. She thought he was unwilling, apathetic, and selfish towards his democratic duty to the country.

A few days later, Sofia – knowing well that she always respected Bob’s intelligence – started questioning her own perception of Bob’s unwillingness to vote. Wanting to know the reason behind his actions, she approached him.

Bob genuinely didn’t feel that any of the candidates were fit to do justice to the role. Hence, with a clear conscience, he chose to exercise his right to refrain from voting, considering his non-vote a protest.

Here, Sofia used her voice of possibility to reach out to Bob and understood his perspective, even though she didn’t agree with Bob’s decision. She understood the complexity behind Bob’s actions, and despite the argument, their friendship is still intact.

This example shows that speaking up for oneself and giving others a fair chance to do the same helps in understanding the reasoning behind one’s perspectives and actions – even when one agrees to disagree.

Questions Are Pathways

If we take the game of Battleship as an example, both players cannot see their opponent’s grid. By asking a series of questions, one has to locate the ships on the opponent’s grid and sink them.

In a similar manner, questions work as essential toolkits or pathways to having productive disagreements and solving them. Questions help in revealing anxieties, opening up perspectives, broadening understanding, inciting empathy, and at times, even helping to find solutions.

However, people tend to use questions poorly. People tend to ask closed questions during disagreements, which are aimed and calibrated at shutting down discussion and dialogue. Other times, people tend to ask questions that emphasise and validate their own perspectives. Essentially, during disagreements, people use the same strategy as the game of Battleship, aiming to sink the discussion completely and win.

People can use the questioning strategy they use in the game Twenty Questions instead. The aim of the game is to probe and ask powerful questions that will help reveal the thing the opponent is thinking about. The game works best when questions are open-ended, imaginative, and unexpected. It discourages participants to ask questions that have one single answer in mind.

Battleship questions, as opposed to the Twenty Questions strategy, hold an iron grip on the dialogue rather than open up space for positive disagreeing.

Consider two friends, one a committed sceptic and the other a believer of ghosts. In an ensuing conversation, the sceptic can ask, ‘What did you experience to believe in ghosts?’ rather than, ‘What proof do you have of the existence of ghosts?’ the second question, rather than ‘sinking the ship’, aims at illuminating the perspective of the believer.

A disagreement with a space to understand others perspectives can even foster closeness between friends. Such light-heartedness can be given to high-stake conversations such as political ones too. The key is to only ask the right questions.

Choosing A Strong debate Partner

In debates, a strategy called nutpicking works wonders. The idea is to pick the opponent with the nuttiest, silliest arguments and then counter-argue that one by one. However, the strategy thwarts interpersonal communication, personal growth and one loses the opportunity to have a productive disagreement.

A productive disagreement needs another tactic. Choosing the wisest and most credible opponent and engaging with them in a challenging debate, actually proves to be a challenge in itself, resulting in a different, unexpected perspective of one’s own argument. On the other hand, challenges to one’s own argument could also lead to strengthening it and broadening one’s own horizons.

Such a level of the debate can also alert one to blind spots and loopholes in one’s own reasoning. A famous story by W.W. Jacobs, called ‘The Monkey’s Paw’, is a great example of why one has to guard against loopholes in one’s own logic.

In the story, a couple is given a magical monkey’s paw. They are told that the paw will grant them any wish, except for one catch. The paw will look for loopholes in the wish and grant the wish in a way different than the intention of the wisher.

The couple, ignoring the disclaimer, decided to try the magic of the paw. They wished for money enough to pay off all their debts. The very next day, their son gets killed in a workplace accident. The compensation they receive is exactly the amount that they require to pay off all debts!

In a debate, one has to seek their ‘monkey’s paw’ – an opponent so skilled that their own loopholes and flaws are highlighted. A debate is a truly challenging one, only when the opponent proves to be a worthy sparring partner!

Having A Neutral Environment

The surrounding environments of an argument are as vital as its content. Spaces are very important factors in influencing disagreements. If we look at a classroom setup, we find that debates happen face-to-face. Additionally, there are rules that students need to abide by and adhere to, and a teacher present to adjudicate.

On the other hand on social media, the consequences of the same topic discussed in a classroom set-up can be different. In such a setting, there is no authority to adjudicate or monitor responses. Social media is a more democratic space, yet more anarchic at the same time. Context can largely influence an argument.

What, then, could be an ideal space for an argument?

- Irrespective of location (classroom or social media) the best space for any arguments should be neutral.

- Whether physical or mental, the space should allow for different perspectives and ideas.

- Comfort in sharing opinions and in giving feedback is essential.

- Additionally, there should be a culture of open discussion that allows acknowledgement of one’s biases and anxieties.

- Controversial opinion or not, no participant should be removed from the group or forced to leave the space.

- Joining and leaving should be of free will, and without explanations.

- The space should be flexible, having a capacity of evolving like the participants.

- For example, in a physical space, flexibility would mean that the participants could arrange and move furniture so as to make the space more agreeable for a debate.

- A digital manifestation of a neutral space would include allowing participants to express themselves – by using emojis or developing an ‘internet-speak

- The space should, finally, be adapting to fit the needs of participants.

A neutral space always harbours productive disagreements; hence creating a neutral space becomes essential.

Ignoring Doesn’t Help

Engaging in productive disagreements is easiest for benign issues, such as choosing a restaurant. It’s less easy, yet most productive for critical issues such as politics. However, ensuring a productive dialogue for hot-button topics such as gun control is most difficult. This is because, with ideas that incite extreme feelings or seem dangerous or repellent, it is extremely difficult to engage productively.

The first reaction to a seemingly abhorrent idea is to shut it down with a voice of avoidance. It is natural to not want to get involved in any way and feel it irresponsible to allow even a minute of existence to such ideas.

The truth of the matter is, that feeling this way or even ignoring such ideas doesn’t make them disappear. Unfortunately, shutting down any dialogue on radical and extreme issues only radicalizes them more.

In fact, when it comes to such hot-button dialogues, the best course of action is to accept the presence of dangerous ideas without endorsing them. One has to engage and consider the offending idea with all three categories the head, the heart, and the hands. In doing so, one can understand the logic and rationale that underpins it, emotionally get to the source of the anxiety, and understand how the idea can be useful, perhaps to strengthen one’s arguments against it.

Understanding the idea with the head will help in understanding how the opponent is thinking. Understanding the idea with the heart will help in asking open-ended questions giving an insight into the emotional core of the idea. Understanding the idea with the hands will help in clarifying its utility, allowing demystifying of the appeal of the idea to the opponent.

Conclusion

Unproductive disagreements do pose a clear threat to humanity, especially with hot-button topics. Unable to reach a conclusion on such issues could be catastrophic. Understanding productive disagreement is vital to healthy communication, connecting with others and clearly visualising a positive goal for ending arguments.

Hence, it is the need of the hour to have people who know how to argue well, argue productively, and productively disagree, where everyone wins!