Why Your “Competing Commitments” Are Stalling Your Team

There is a pattern I observe in founders led companies that is quietly stifling their organizations. It is not a lack of skill, and it is not a lack of vision. It is a conflict of identity.

The pattern looks like this: A founder walks into a meeting and casually says, “We should get some case studies from clients.”

To the founder, this is just an idea – a helpful contribution. Whoever hears that idea – no matter how many levels below the founder they sit – treats it as a directive, not an idea.

That directive collides with existing priorities. It creates confusion. It overloads people with tasks that aren’t anchored in a clear problem or purpose. The only real “why” behind it is (when it comes to execution): the founder said so. (even if the founder didn’t mean it like that)

On the surface, this looks like a communication issue. But if we look deeper, we find what organizational psychologists call “Competing Commitments.” You say you are committed to building an autonomous, empowered team. But subconsciously, you are committed to being the person who saves the day.

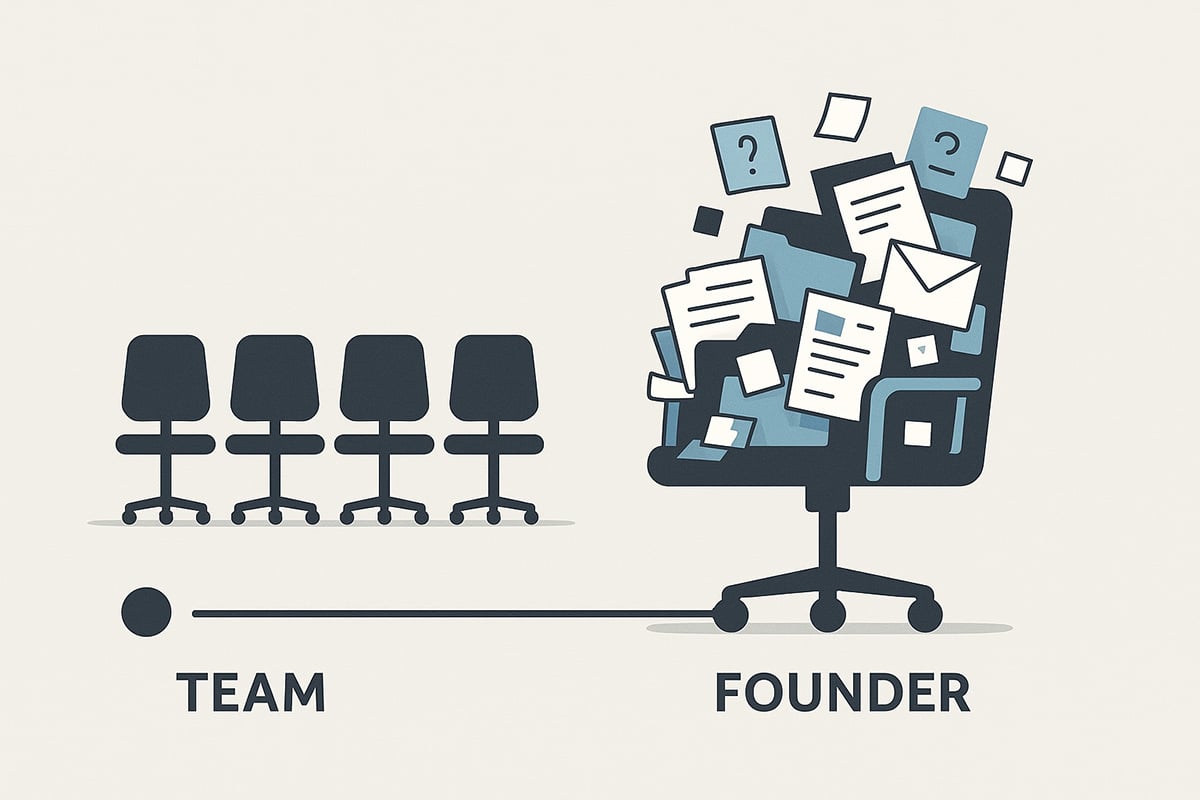

The outcome – chaos, missed deadlines, lack of clarity, misunderstandings, last-minute firefighting, and the whole company being dependent on the founder to save the day.

So What’s Really Happening?

A founder comes across a single piece of information. Perhaps someone tells them something at a conference. It might be something vague like, “People are talking about your company.”

Instead of slowing down and asking, “Which people? How often? What exactly did they say?”—they treat the information as truth.

From there, everything accelerates. They jump to a conclusion: “This is a problem.” They decide the problem requires action: “This is something we need to deal with.” They decide on a solution: “We need some case studies.”

They decide who should do it – and task them directly. All of this happens before anyone else is involved. Before more data is gathered. Before the actual owner of the problem has any say in defining it. One data point becomes a full-blown directive with organizational weight behind it.

The “Artisan” Identity vs. The Enterprise Builder

Chris, owner of Crown Capital, who specializes in transitioning founder-led businesses, describes this perfectly when I recently spoke with him. He notes that many founders get stuck at a specific revenue ceiling because they are running an “Artisan Shop.”

In an Artisan Shop, the founder is the product. They are the best salesperson, the best product designer, and the best problem solver. The business relies entirely on their personal craftsmanship. As Chris points out, “It feels really good to be needed.”

This is the seduction of the Artisan identity. In the early days, your identity was tied to being the engine that made things move. You were the “fixer.” But as the company scales, that same identity becomes a “cul-de-sac”—a dead end where you are running in circles, unable to scale because you cannot scale yourself.

To break through, you have to fundamentally alter your relationship with the company. You must stop viewing the company as an extension of your personal output and start viewing it as a system that you design.

This Isn’t Malicious – The Founders Are Not Doing Anything Wrong

In fact, it’s rooted in something pretty brilliant. To understand why this happens and what can be done about it, you have to begin by looking at how founders see themselves, their role, and their identity. If we treat their actions as a “bad habit to correct,” we miss the point entirely.

Behavior doesn’t change because someone is told to “slow down” or “stop giving solutions.” It changes when they see what’s driving the behavior in the first place. Founders often have commitments running in the background that they don’t fully see:

- A commitment to being useful.

- A commitment to being helpful.

- A commitment to ensuring their people succeed.

- A commitment to adding value.

- A commitment to being essential.

These commitments got them where they are. However, these are the same commitments that are keeping them stuck now.

Even if a founder says they want empowerment, autonomy, and a team that owns problems end-to-end – their deeper commitment, the one they don’t consciously see, can still run the show. Our competing commitments make all of us run on autopilot.

Why This Is So Hard

Keith Rabois, who helped build PayPal, LinkedIn, and Square, has a useful framework here. He learned it from Peter Thiel. The idea is simple: before you get involved in a decision, consider two things. First, how strong is your conviction about the right answer? Second, how significant are the consequences if you’re wrong?

If the consequences are low and your conviction is low, let your team run with it. If the consequences are high and your conviction is high, get involved. But most founders don’t think this way. They treat every decision like it’s high stakes. They jump in everywhere. And over time, their team learns to wait for permission instead of taking ownership.

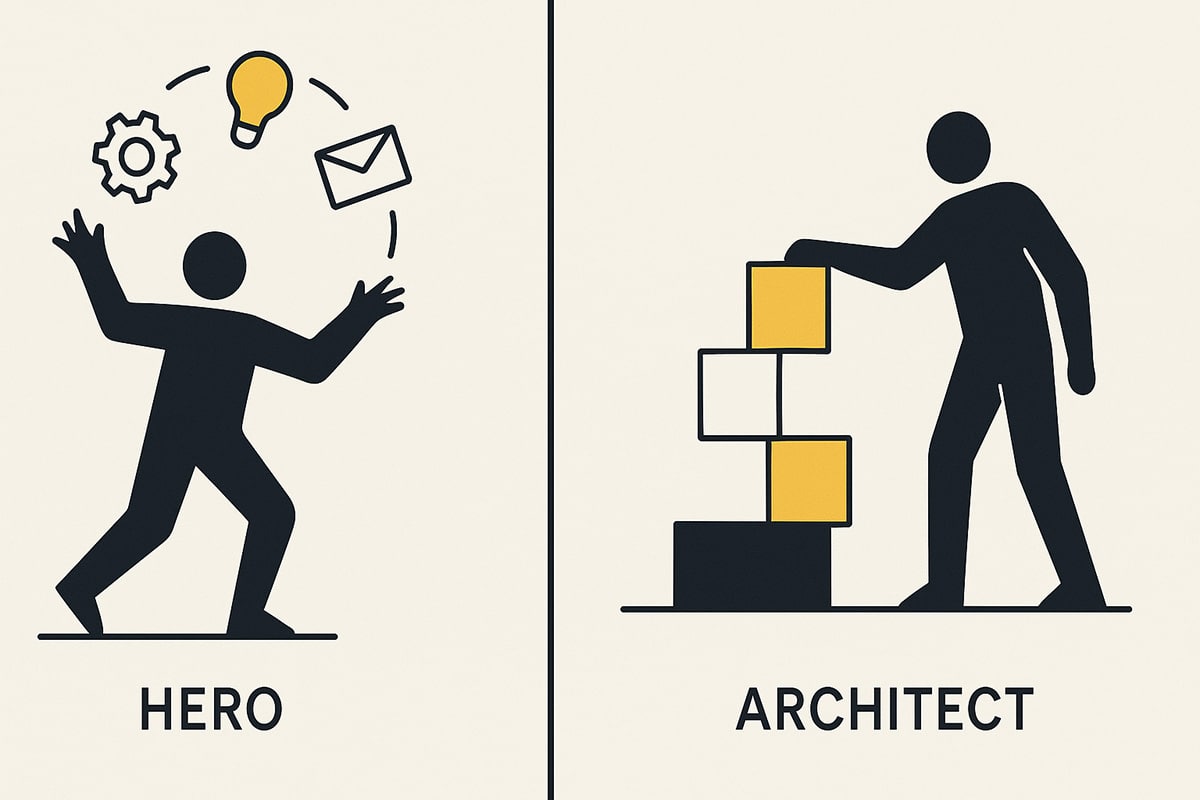

The Shift in Being: From Hero to Architect

Changing behavior (e.g., “I will speak less in meetings”) is rarely enough because behaviors are only symptoms that happen downstream of identity (who you are). If you still identify as the “Hero or the Problem Solver” you will inevitably intervene when things get tough.

You have to shift your state of Being.

Chris shares his own painful transition from being a high-net-worth attorney/consultant to a fund manager. As a consultant, he was the product. To move to the next level, he had to enter “The Dip”—a period of discomfort where he had to stop doing the work that made him feel valuable (billable hours, direct client advice) to invent a new identity as an asset allocator.

He had to stop asking, “How do I solve this?” and start asking, “How do I build a system that solves this?”

This is a crisis of ego. It requires accepting that your value is no longer defined by your direct output.

The Cost Nobody Talks About

Here’s what happens when this pattern runs unchecked.

The team stops thinking. They learn that their job isn’t to solve problems—it’s to wait for the founder to tell them what to do.

The best people leave. Not because they don’t believe in the mission, but because they’re tired of being treated like executors instead of leaders.

The founder becomes the bottleneck. Everything runs through them because that’s what the organization has learned to expect.

The founder burns out. They can’t understand why nobody else steps up—when in reality, they’ve trained the whole company not to.

And none of this is visible to the founder. Because from their perspective, they’re just being engaged. Responsive. Helpful.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Next time you hear a piece of information or feel the urge to act, pause. Ask yourself: Am I about to make this my problem to solve?

If the answer is yes, stop. Then ask:

Whose problem is this, really? Not who should solve it — who actually owns this domain?

Separate what happened from what you’re making it mean from what you’ve already decided to do.

What would it look like if I held space instead of solving this?

That might mean bringing the issue to the right person and asking, “What do you make of this?” It means staying engaged without taking over.

This will feel uncomfortable. It’ll feel like you’re not adding value. Like you’re being passive.

You’re not.

You’re teaching your team that they’re capable. You’re building their ownership. You’re creating space for them to rise.

This shift requires new practices that force you to step out of the “Artisan” role.

1. The Bezos Decision Framework

Most founders treat every decision as a crisis that requires their “Hero” identity. Jeff Bezos counters this by distinguishing between Type 1 (irreversible) and Type 2 (reversible) decisions.

The “Artisan” founder treats everything as Type 1. The “Architect” founder realizes that 90% of decisions are Type 2. By recognizing that most doors are two-way, you can suppress the urge to intervene, allowing the team to own the risk and the learning.

2. The Munger Inversion

Chris utilizes a technique from Charlie Munger called “Inversion.” Instead of asking, “How do I help my team succeed?” ask, “What would I do if I wanted to ensure my team remains helpless?”

- Answer: I would solve every hard problem for them. I would correct their work before they finish it. I would make every decision myself.

- Realization: By doing these things, you are actively sabotaging the autonomy you claim to want.

3. Creating “Thinking Space”

You cannot shift your identity if you are constantly reacting. Chris implemented a rigorous practice of blocking out Thursday afternoons entirely. No meetings, no calls—just “block production time” to think. (My interview with Chris will come out early next year – 2026)

If you are always on the treadmill of execution, you are acting as an employee of your own company, not its leader. You need space to detach from the “doing” so you can work on the “being.”

A New Relationship With Your Business

There’s something else worth naming here. As a company grows, the founder’s relationship with it has to change. What worked at twenty people breaks at two hundred. The intimacy that once held everything together can become the very thing that holds it back.

This isn’t failure. It’s evolution.

The founder who built the startup has to become the leader who builds the institution. And that requires letting go of being needed in the old ways while finding new ways to matter. This is one of the loneliest transitions in leadership. And it’s rarely talked about.

The Audit:

To make this shift real, you need a feedback loop.

- Find a Truth-Teller: Give a trusted partner permission to interrupt you. “If you see me playing the Hero, call it out.”

- The Weekly Reflection: Ask yourself, “What did I take ownership of this week that wasn’t mine?”

You have to let go the loss of your old identity – the one that saved the day, the one that knew all the answers. That version of you was essential to get the company from $0 to $2 million. But that version of you is now the primary obstacle getting from $2 million to $20 million.

Your team doesn’t need a savior. They need a leader who believes they can save themselves.

Leave a Reply