Have you ever noticed how some leaders seem to create results out of thin air while others struggle to move the needle despite working twice as hard?

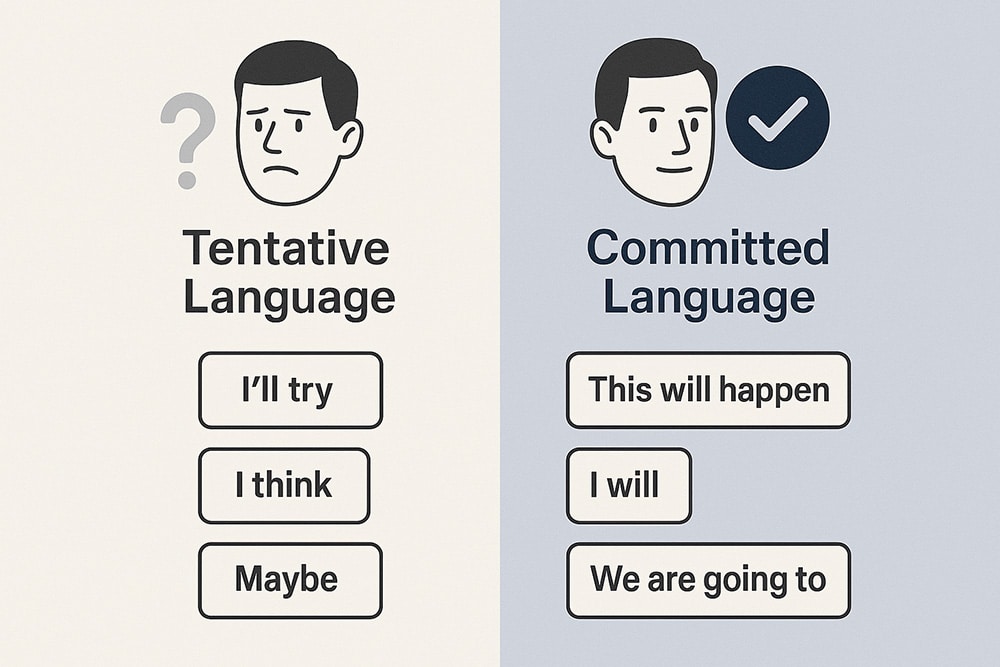

The difference often isn’t found in their strategies, intelligence, or even work ethic. It’s hidden in their language – specifically, whether they speak and then act with commitment or tentativeness when addressing the future.

Let me share what I witnessed in a fascinating leadership session that revealed this crucial distinction. A group of managers was exploring why they habitually used phrases like “I’ll try,” “I hope,” or “Let me see what I can do” – even when they fully intended to complete the task.

Their answers revealed something profound about how most of us operate:

“I’m buying time to make sure I can deliver.” “I don’t want to disappoint people if I can’t follow through.” “I’m avoiding taking full responsibility.” “I’m protecting myself from looking wrong.”

Sound familiar? These are the unconscious calculations we make dozens of times daily.

But here’s the twist: these seemingly harmless verbal cushions aren’t just communication quirks – they fundamentally shape how we think, act, and ultimately, what we achieve.

The Hidden Cost of “I’ll Try”

When you say “I’ll try” instead of “I will,” you’re not just being cautious. You’re unconsciously programming your mind and actions for uncertainty. This tentative language carries hidden costs:

- Mental burden and constant background stress

- Scattered attention and divided focus

- Lower productivity and action velocity

- More time spent in indecision and doubt

- Uncertainty for everyone involved

As one participant confessed: “When I say I’ll try, I end up working overtime to accommodate everything, constantly juggling priorities, and feeling perpetual stress because I’m not clear about what I’m fully committing to.”

Another revealed: “I find myself overthinking and second-guessing instead of just executing. It’s exhausting.”

These aren’t just personal inconveniences. They represent a massive tax on your leadership energy – energy that could be directed toward creating breakthrough results.

It is not just Semantics

Language shapes thought. Thought drives action. Action creates results. This causal chain, supported by decades of neurolinguistic research, explains why the words leaders choose don’t merely describe their intentions—they fundamentally shape what becomes possible for themselves and their organizations.

As Dr. Guillaume Thierry notes in his groundbreaking research on neurolinguistic relativity, “Language influences—and may be influenced by—nonverbal information processing.” This isn’t about linguistic tricks or superficial changes to your vocabulary. It’s about understanding and harnessing the profound connection between language, thought, and action—a connection that lies at the heart of truly transformational leadership.

When a leader says “We will launch this product by Q3,” they’re not just making a prediction—they’re performing what linguists call a “commissive speech act” that creates a social commitment. This commitment changes the relationship between the speaker and listeners, establishing new expectations and permissions that shape subsequent behavior.

In contrast, when a leader says “We hope to launch this product by Q3,” they’re performing what linguists call an “expressive speech act” that merely describes their current mental state without creating new social commitments. This distinction explains why teams respond so differently to committed versus tentative leadership language—the former creates new social realities that drive action, while the latter merely comments on existing realities.

The Liberation of Clear Commitment

Now consider the alternative. What happens when you simply say “This will happen” or “I will deliver this” – even before you have all the evidence that you can?

The same participants described:

- Mental clarity and inner peace

- Heightened productivity

- Optimal use of time

- A healthier communication environment

- Faster, more decisive action

One leader noted: “When I commit clearly, I don’t waste time debating with myself. I just find a way to make it happen.”

This is the power of committed language – it creates a different foundation from which you operate and take action. Instead of waiting for certainty before committing, you commit first and then create the certainty through your actions.

When leaders use committed language, they’re not just expressing confidence—they’re creating psychological conditions that automatically trigger action when relevant situations arise, without requiring additional decision-making or motivation.

The psychological power of committed language extends beyond individual cognition to social dynamics. Dr. Robert Cialdini, whose research on influence has transformed our understanding of persuasion, identifies commitment and consistency as one of the fundamental principles of human behavior. Once people make a clear commitment, they experience both internal and external pressure to behave consistently with that commitment.

This commitment-consistency principle explains why leaders who make clear, public commitments using committed language are significantly more likely to follow through than those who use tentative language. The psychological and social forces activated by committed declarations create momentum toward the declared outcome that tentative statements simply cannot generate.

The Courage to Look Wrong

At this point, you might be thinking: “But what if I commit and fail? Isn’t it more honest to say I’ll try?”

This is where courage enters the picture. The truth is, there’s no evidence in the future – only in the past. When you commit to something unprecedented, something you’ve never done before, you’re stepping into territory where failure is possible.

Most people avoid this risk at all costs. They want guarantees before they commit. But that’s precisely why most people don’t create extraordinary results.

Leaders who produce unprecedented outcomes understand a fundamental truth: commitment precedes evidence. They don’t wait for proof they can deliver before they commit – they commit first, then find a way to deliver.

Yes, sometimes they’re wrong. Sometimes they fail. But they understand that the occasional pain of being wrong is far less costly than the chronic pain of playing small.

Fear of Disappointment: Many leaders use tentative language to manage expectations—both their own and others’. By saying “I’ll try” rather than “I will,” they create a psychological buffer against the pain of disappointing themselves or others if they fail to deliver.

James, a senior executive at a technology company, recognized this pattern in himself: “I realized I was saying ‘I’ll try’ even when I fully intended to complete the task. It was a way of giving myself an out, of protecting myself from the potential disappointment of failure.”

Fear of Judgment: Leaders often worry that clear commitments will expose them to harsher judgment if they fall short. Tentative language creates plausible deniability—”I only said I would try”—that shields them from full accountability.

Research in social psychology confirms this dynamic. A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that individuals who used tentative language were judged less harshly for identical failures than those who had made clear commitments. This creates a perverse incentive for leaders to hedge their language, even when doing so undermines their effectiveness.

Fear of the Unknown: Perhaps most fundamentally, leaders fear committing to outcomes when they cannot see the full path to achievement. This fear of the unknown drives them toward tentative language that preserves optionality and avoids the discomfort of certainty in uncertain conditions.

Dr. Carol Dweck’s research on mindset provides insight into this fear. Leaders with a fixed mindset—who believe capabilities are static rather than developable—are particularly prone to fear of the unknown. They worry that they may not have the skills or resources to fulfill clear commitments, so they hedge with tentative language.

The Paradox of Leadership Fear

The paradox of leadership fear is that the very language patterns that protect leaders from these fears also prevent them from achieving their full potential. By using tentative language to avoid the risk of being wrong, leaders create conditions that make success less likely and limit what’s possible for themselves and their organizations.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: fear leads to tentative language, which leads to diminished results, which reinforces the fear that clear commitments are too risky. Breaking this cycle requires understanding that the apparent safety of tentative language is illusory—it protects you from the risk of being wrong at the cost of ensuring you’ll never be transformatively right.

The Two Operating Systems

Think of these approaches as two distinct operating systems for leadership:

Operating System 1: Evidence-Based Commitment

- Wait for evidence before committing

- Use tentative language to protect yourself

- Avoid disappointing others

- Reduce risk of being wrong

- Create predictable, incremental results

Operating System 2: Commitment-Based Evidence

- Commit first, then create the evidence

- Use clear, direct language

- Accept that some may be disappointed

- Accept the risk of being wrong

- Create unprecedented, breakthrough results

Most leaders operate exclusively in System 1. They believe it’s the only responsible way to lead. But what they don’t realize is that System 1 has built-in limitations – it can only produce results that are extensions of what’s already been done.

System 2 is where unprecedented results come from. It’s where you find the leaders who transform industries, redefine what’s possible, and create outcomes that seemed impossible before they arrived.

The Language Patterns of Each System

The distinction between these operating systems is most clearly revealed in language patterns. Leaders operating in Evidence-Based Commitment tend to use:

- Tentative language: “We’ll try,” “We hope to,” “We expect”

- Conditional statements: “If X happens, then we’ll do Y”

- Probability-based phrasing: “There’s a good chance,” “It’s likely that”

- Hedging qualifiers: “Assuming all goes well,” “Barring unforeseen circumstances”

In contrast, leaders operating in Commitment-Based Evidence consistently employ:

- Declarative statements: “We will,” “This is going to happen”

- Time-bound commitments: “By this date,” “Within this timeframe”

- Certainty-based phrasing: “This will work,” “We are going to succeed”

- Unequivocal language: “No matter what,” “Whatever it takes”

These language patterns aren’t merely stylistic differences—they reflect and reinforce fundamentally different approaches to leadership and possibility. By becoming aware of your own language patterns, you can begin to shift from System 1 to System 2 in the areas where breakthrough results matter most.

The Personal Challenge

One participant shared his personal struggle with this concept:

“I have a long history of blaming myself when things go wrong. I worry that if I commit strongly and then fail, I’ll spiral into self-blame.”

This is a legitimate concern. But notice what’s happening here – the fear of future self-blame is preventing bold commitment in the present.

The solution isn’t to avoid commitment. It’s to develop a healthier relationship with mistakes and failures. As this leader discovered, daily practice in reframing mistakes as learning opportunities gradually reduced his tendency toward self-blame.

He shared: “I started practicing positive daily declarations and focusing on what I can learn from mistakes rather than internalizing them. This has drastically reduced my stress and improved my productivity.”

This inner work is essential. You cannot speak with powerful commitment externally if you’re plagued by self-doubt and harsh self-judgment internally.

Distinguishing Accountability from Self-Blame

A critical distinction for leaders developing the courage for committed language is between healthy accountability and unhealthy self-blame. Both involve taking responsibility for outcomes, but they create fundamentally different psychological conditions for committed language.

The Neuroscience of Self-Blame

Neuroscience research reveals that self-blame activates brain regions associated with shame and avoidance, creating a neurological state that naturally drives tentative rather than committed language. When leaders engage in self-blame after failures, they neurologically prime themselves to hedge future commitments.

In contrast, healthy accountability activates brain regions associated with problem-solving and approach motivation, creating a neurological state conducive to clear, decisive action.

When to Say No

Another crucial aspect of committed language is learning to say a clean, clear “no” when appropriate.

One leader confessed: “I say ‘I’ll try’ when I actually want to say no, because I don’t want to hurt or disappoint people.”

This is where empathy without authenticity becomes weakness. When you say “I’ll try” instead of “no,” you’re not being kind – you’re being unclear. You’re creating false hope and ultimately more disappointment than a clear no would have caused.

“Empathy without authenticity is weakness. Leadership is doing what is required, not what is easy.”

A clean no is far more respectful than a vague, uncommitted maybe. It allows the other person to make clear decisions based on accurate information rather than false hope.

The False Kindness of “Maybe”

When faced with requests they don’t intend to fulfill, many leaders default to tentative responses: “Maybe later,” “I’ll see what I can do,” or “Let me think about it.” They believe these responses are kinder than a direct “no,” sparing the requester immediate disappointment.

This belief, while well-intentioned, reflects what psychologists call the “empathy-accuracy trade-off”—the mistaken assumption that being kind requires being vague or even misleading. Research in communication psychology reveals that this approach actually creates more harm than good.

Dr. Brené Brown, whose research focuses on vulnerability and leadership, explains: “Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind. When we use vague, tentative language instead of a direct ‘no,’ we’re not being kind—we’re avoiding our own discomfort at the expense of the other person.”

This avoidance creates several significant problems:

- False hope: The requester often interprets tentative language optimistically, creating expectations that will eventually be disappointed.

- Wasted energy: Without clear boundaries, requesters may continue investing time and emotional energy pursuing something that won’t happen.

- Delayed disappointment: The disappointment isn’t eliminated—it’s merely postponed, often to a point where the stakes and expectations are higher.

- Eroded trust: When patterns of tentative “maybes” consistently become eventual “nos,” trust in your communication deteriorates.

The Practice of Commitment

Transforming your language from tentative to committed isn’t an overnight change. It’s a practice – one that feels uncomfortable at first, especially if you’ve spent years or decades operating from System 1.

Here’s how to begin:

- Notice your language patterns. Pay attention to how often you say “I’ll try,” “I hope,” or “Let me see.” Just observing these patterns creates awareness.

- Start with low-stakes commitments. Practice committed language in areas where the consequences of failure are minimal. This builds your comfort with commitment.

- Examine your fears. When you catch yourself using tentative language, ask: “What am I afraid might happen if I commit clearly here?”

- Separate identity from outcomes. Remember that failing at something doesn’t make you a failure. It makes you someone who took a risk.

- Create morning intentions. As one participant shared: “I write down my intentions for the day – how I want to show up, what I’m committed to accomplishing. This primes my mind for clear commitment.”

The Leadership Choice

Every day, in countless conversations, you choose how you’ll speak about the future. Most of these choices happen unconsciously, driven by habits and fears you may not even recognize.

But now you have a choice. You can continue operating exclusively from System 1 – waiting for evidence before committing, protecting yourself from being wrong, and creating predictable results.

Or you can begin incorporating System 2 – committing before you have all the evidence, accepting the risk of being wrong, and creating the possibility of unprecedented outcomes.

This isn’t about abandoning careful thinking or responsible planning. It’s about recognizing that for the results that matter most – the breakthrough innovations, the transformative changes, the unprecedented achievements – commitment must precede certainty.

The Spectrum of Commitment

It’s worth noting that this isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition. You don’t have to commit with absolute certainty to everything. Think of it as a spectrum:

- For routine, low-impact decisions: Your habitual approach may work fine

- For moderate-impact decisions: Consider more committed language

- For high-impact, transformative goals: Full commitment is essential

I’m not asking you to jump totally to committed language for everything. But for the things that matter, for the results that matter, you commit. And yes, you can be wrong. And that’s the cost of taking on any big game.

Your Unprecedented Future

Look at the goals you’re currently pursuing. The ones that really matter. The ones that would transform your leadership, your organization, or your life.

Now ask yourself honestly: Am I speaking about these goals with committed language or tentative language?

Am I saying “I’ll try to hit our targets” or “We will hit our targets”?

Am I saying “I hope to transform our culture” or “I will transform our culture”?

Am I saying “Let’s see if we can innovate” or “We will innovate”?

The difference may seem subtle, but it’s everything. In that small linguistic gap lies the difference between leaders who manage the status quo and leaders who create new realities.

The Time for Commitment

Most of us have been conditioned to believe that certainty should precede commitment – that we should only promise what we’re already certain we can deliver.

But that approach has built-in limitations. It confines you to the realm of the proven, the established, the already-done. It makes unprecedented results impossible by definition.

The greatest leaders throughout history have operated differently. They committed to outcomes that seemed impossible at the time:

- Landing on the moon before the technology existed

- Creating computers that fit in our pockets before the components were invented

- Building electric vehicles viable for mass markets before the infrastructure was in place

None of these commitments were “reasonable” when they were made. All required their leaders to stand in a place of commitment before evidence existed.

You have this same power available to you right now. The power to commit to a future that doesn’t yet exist – and through that commitment, begin creating it.

Yes, you might be wrong sometimes. Yes, you might disappoint people occasionally. Yes, you might look foolish in the eyes of those who operate solely from System 1.

But you also might create something unprecedented – something that changes everything.

Isn’t that possibility worth the risk?

The Choice Before You

So here’s the invitation: Choose one important goal – something that matters deeply to you, something that would represent a breakthrough in your leadership or organization.

Now, how do you speak about this goal? With tentative, cautious language? Or with clear, committed language?

If you’re like most leaders, you’ve been operating from System 1 – waiting for certainty before committing. That’s not wrong, but it is limiting.

What would happen if you shifted to System 2 for this one crucial goal? If you spoke with commitment before you had all the evidence? If you said “This will happen” instead of “We’ll try to make this happen”?

You might fail. You might be wrong. You might disappoint yourself or others.

Or you might create something unprecedented – something that changes everything.

The choice is yours.

The journey of committed language begins with a single, powerful choice: the decision to speak with clarity and certainty about the future you will create. This choice—to replace “I’ll try” with “I will”—seems simple on the surface but represents a profound shift in how you relate to possibility, responsibility, and your own capacity for impact.

In making this choice, you join a lineage of transformational leaders throughout history who have used the language of commitment to create unprecedented futures. From Churchill’s defiant “We shall never surrender” to Kennedy’s bold “We will go to the moon” to your own declarations about what will happen in your organization, committed language (or the lack of it) shapes your future.

Your future is waiting.

Leave a Reply