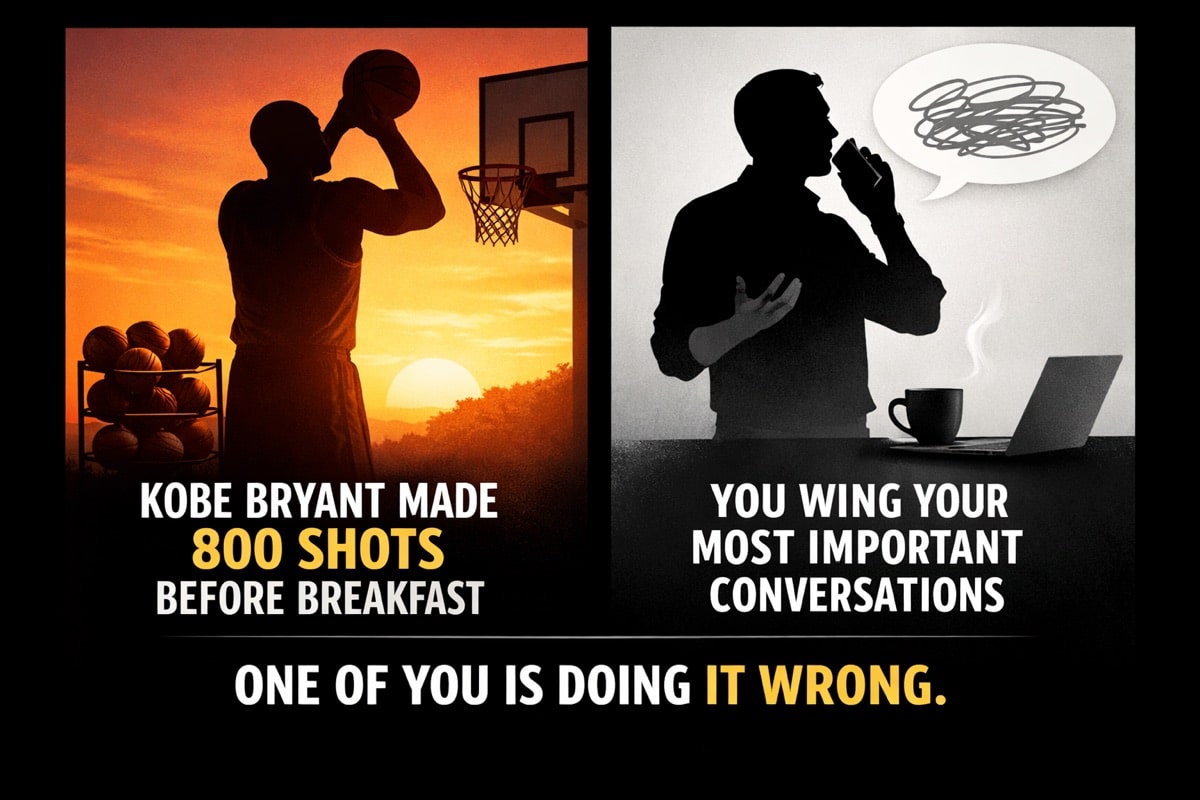

Kobe Bryant made 800 shots before breakfast. You wing your most important conversations. One of you is doing it wrong.

During Team USA training camp, Kobe called a trainer at 4:30 in the morning. He ran conditioning drills until 6. Lifted weights until 7. Then shot baskets until he made 800 of them – not attempted, made – before the team’s official practice even started.

By the time his teammates arrived for the first drill, Kobe had already done more work than most players did in a full day. He won games because he prepared at a level that made the game itself feel easy.

But here’s what nobody talks about: this isn’t just a sports thing.

The best leaders in business do the same thing. They practice. Not occasionally. Not when they feel like it. Deliberately, granularly, obsessively.

Greatness requires repetition. And most leaders don’t practice at all.

The Problem: We’ve Confused Repetition with Practice

You’ve had a hundred difficult conversations. You’ve coached struggling employees. You’ve negotiated deals and handled conflict and tried to inspire your team.

But doing something repeatedly isn’t the same as practicing it.

Practice is deliberate. It’s isolated. It’s focused on getting better at a specific skill under controlled conditions. It happens when nothing is at stake so you’re prepared when everything is.

Athletes understand this intuitively. Kobe didn’t practice his fadeaway jumper during the fourth quarter of the Finals. He drilled it ten thousand times in an empty gym so that when the pressure was on, his body already knew what to do.

Leaders? We “learn on the job.”

That’s a polite way of saying we treat every high-stakes moment like a first draft. We walk into boardrooms, investor pitches, difficult terminations, and crisis situations having never practiced the specific skills those moments require.

Then we wonder why leadership feels so hard. Or why you end up creating a mess and cleaning it up later.

Leadership Is a Set of Practiceable Skills

Let’s be specific about what you’re not practicing:

Speaking boldly. Not in the meeting. Before it. Record yourself delivering the hard truth you need to say. Listen to it. Notice where you hedge, where you apologize, where you dilute your point. Do it again. Most leaders practice being diplomatic. Champions practice being direct.

Breathing and centering. You can’t regulate your nervous system in real-time if you’ve never practiced doing it when you’re calm. Athletes train their breathing for years. On the other hand, I have seen many leaders hyperventilate through Zoom calls and calling it “intensity.”

Empathy. You think empathy is about being nice. It’s not. It’s about accurately reading what someone else is experiencing and responding to the real problem, not the surface one. That’s a skill. You can practice it by role-playing situations and forcing yourself to name the emotion you’re observing before you respond.

Resisting the urge to interrupt. This one’s simple. In practice conversations, put a physical object in your hand and don’t speak until the other person has finished and you’ve counted to three. Your ego will hate this drill. That’s how you know it’s working.

Listening. Real listening – the kind where you’re actually trying to understand, not just waiting for your turn to talk – is unnatural for most leaders. Not because it is difficult. Not because of instagram notifications. Or Tiktok. Because you have not practiced it enoughl. Practice it by having someone tell you a problem and then forcing yourself to ask three clarifying questions before offering any solution.

Deal making. You don’t negotiate your biggest deal cold. You role-play it. You practice the concessions you’re willing to make, the points you won’t budge on, the moments where you’ll walk away. You rehearse staying silent after you make an offer.

Dealing with bullies. You will encounter people who try to dominate you through aggression, condescension, or manipulation. If you haven’t practiced staying grounded and non-reactive when someone’s in your face, you’ll either collapse or escalate. Neither is leadership.

Inspiring people. You think inspiration is spontaneous. It’s not. It’s clarity about what matters, delivered with conviction at the right moment. You can practice this. Write down what you actually believe about your work, then practice saying it out loud until it doesn’t sound rehearsed.

Coaching people. Most leaders give advice when they should be asking questions. Practice coaching by forcing yourself to only ask questions for the first five minutes of a conversation. No statements. No suggestions. Just questions that help the other person think more clearly.

These aren’t abstract concepts. They’re practiceable skills.

The Mountain with No Top

Here’s what makes leadership different from almost any other skill: there’s no finish line.

You don’t “complete” empathy training and move on. You don’t “master” inspiring people. Leadership is a mountain with no top. No matter how good you are at something, you can always practice more and get better at it.

And here’s the paradox: the people who practice the most aren’t the rookies. They’re the champions.

Kobe practiced more than the guys fighting for a roster spot. Buffett has read more investor letters than junior analysts will read in their entire careers. The best leaders don’t coast on their experience. They obsessively sharpen the skills that got them there.

Most business leaders do the opposite – especially when it comes to leadership and people skills. They treat “experience” as if repetition alone makes them better. But repetition without reflection is just rehearsing your mistakes.

You’re not getting better at difficult conversations by having more of them badly. You’re just reinforcing bad habits.

How to Actually Practice Leadership

Here’s the framework:

1. Isolate the skill. Don’t try to “get better at leadership.” Pick one granular skill. This week, it’s resisting the urge to interrupt. That’s it.

2. Create low-stakes repetitions. Role-play with a peer. Record yourself. Practice in conversations that don’t matter. The point is to build the muscle memory before the high-pressure moment arrives.

3. Get feedback. You can’t see your own blind spots. Ask someone to watch you practice and tell you what you’re missing. Athletes have coaches for this reason.

4. Increase the difficulty. Once you can stay centered in a calm practice conversation, practice staying centered when someone’s deliberately trying to trigger you. Make the drill harder until it’s harder than the real thing.

5. Repeat until it’s automatic. You’re not done practicing when you can do it right once. You’re done when you can’t do it wrong. When your nervous system responds correctly before your brain even catches up.

That’s the standard. and today, AI can help you practice all of that.

The Unfair Advantage

The gap between good leaders and great ones isn’t intelligence. It’s not charisma. It’s not even strategy.

It’s that great leaders turn more of their life into a practice that nobody else sees.

They practice breathing before the meeting starts. They role-play difficult conversations with a trusted peer. They drill staying non-reactive when someone’s being an asshole. They rehearse inspiring people until their conviction sounds natural, not performative.

They do the work when nothing’s at stake so that when everything’s at stake, their body already knows what to do.

You’re not going to get better at leadership by reading more books or attending more conferences or gaining more “experience.”

You’re going to get better by practicing the specific skills you’re currently winging.

Pick one. Breathing and centering. Speaking boldly. Listening without interrupting. Coaching instead of advising.

Then practice it like Kobe practiced his basketball skills.

The game feels hard because you never rehearsed for it. Not because the game (or your job) is hard.

Now go practice.

Leave a Reply