There’s a pattern I see in certain companies that’s puzzling at first glance.

The CEO is a very nice and kind person. Genuinely kind. The kind of person people respect deeply and stay loyal to for decades. They’ve built a team of exceptional people around them. Each one of them can be called superstars by any measure.

And yet.

Those superstars play against each other. They form factions. They undermine one another in meetings. They gossip. They politic. They spread negativity behind closed doors. I have now seen it in too many companies to call it a “pattern”.

As a result, the culture suffers. Performance of the company suffers. And if the company suffers, each individual superstar is also suffering. But – alas – they can not see that. They continue pointing fingers at others and getting defensive when a finger is pointed at them. They are all losing – because the company is losing – and yet they think that they are each performing well.

From the outside, it doesn’t make sense. Great leader. Great people. Terrible dynamics.

But when you look closer, it makes perfect sense.

The Question Nobody Wants to Ask

When a team is dysfunctional, the natural instinct is to look at the team.

“These people are too competitive.”

“They have ego problems.”

“They’re not team players.”

But that’s rarely the whole story.

The harder question is: What is the founder or the CEO doing – or not doing – that makes this behavior possible?

Because here’s the thing. Smart people don’t engage in politics for fun. They do it because something in the system rewards it. Or at least doesn’t punish it.

So if you’ve got a team of brilliant people acting like rivals instead of partners, something in the environment is allowing it. And that environment starts at the top.

What’s Really Going On

To understand this, you have to look at how the CEO sees themselves, their role, and their relationship with conflict.

If we treat the team’s behavior as the problem to fix, we miss the point entirely.

The CEO likely has commitments running in the background – commitments they don’t fully see. These commitments feel like virtues. They probably are virtues. But left unexamined, they create the exact conditions for dysfunction. These commitments create a “pattern” of behavior for the founder/CEO that then leads to the pattern we see with the team.

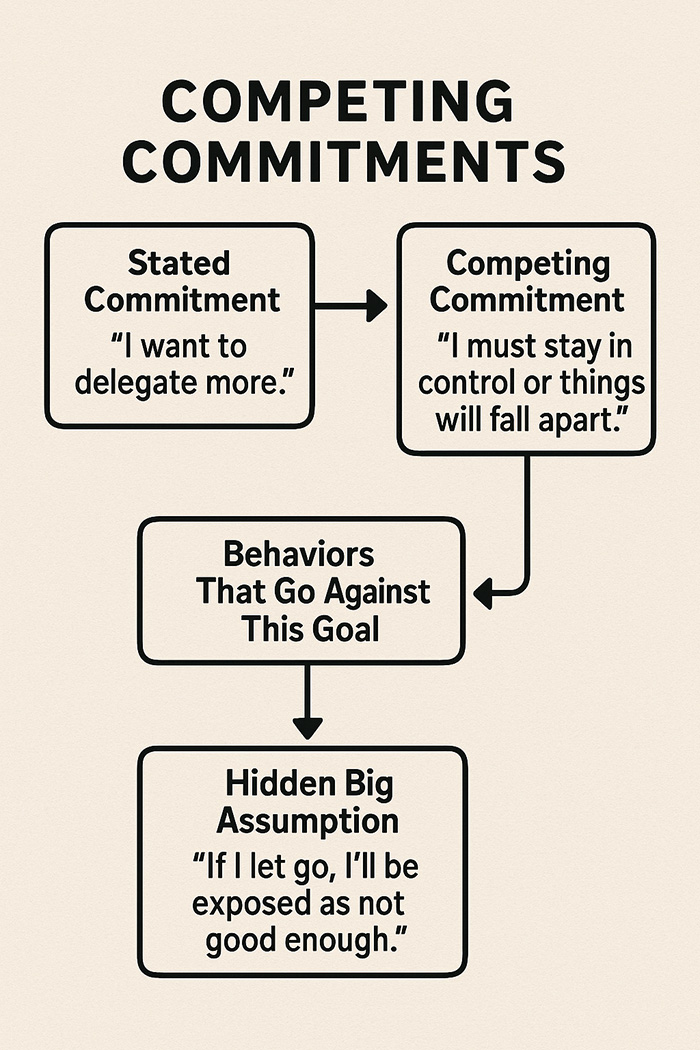

These commitments are what the Harvard psychologist Robert Kegan calls the Competing Commitments (from his & Lisa Lahey’s work on the book “Immunity to Change”) . They are the hidden commitments you made to yourself long ago that now quietly competing with your biggest goals.

Here are some of the competing commitments I find in these companies and their leaders:

(one or many of the below might be applicable for you)

A Commitment to Being Liked

Kind leaders want people to feel good around them. They want to be seen as fair, caring, approachable.

The other side of it? They avoid hard conversations.

When two superstars are at war, the kind CEO might hope it resolves itself. They might talk to each person privately but never bring them into the same room. They smooth things over instead of naming the real issue. They avoid taking sides because someone might get hurt.

The result? Nothing gets resolved. The conflict goes underground. It becomes hallway conversations and political maneuvering instead of direct confrontation.

The CEO thinks they’re keeping the peace. They’re actually teaching the team: We don’t deal with conflict here. You’re on your own.

A Commitment to Being Fair

Kind leaders bend over backwards to be equitable. They don’t want anyone to feel favored or overlooked.

The other side? They refuse to make clear calls.

They won’t publicly say, “This is the direction we’re going.” They won’t back one leader’s approach over another, even when the situation demands it. They keep things open-ended in the name of fairness.

So what do the superstars learn? The CEO won’t decide. Which means I have to win through other means.

That’s when politics becomes rational. If the boss won’t pick a direction, the team will fight it out amongst themselves – through influence, alliances, and undermining each other.

A Commitment to Harmony

Some leaders believe that good teams shouldn’t have conflict. That if people are fighting, something is wrong.

The other side of it? They suppress tension instead of working through it.

They shut down debates too early. They change the subject when things get heated. They privately ask people to “be more collaborative” instead of letting the team wrestle with real disagreements.

The result? The real conversations happen outside the room. People learn that the only way to be heard is through back channels.

That’s not politics because people are bad. It’s politics because the front door is closed.

A Commitment to Loyalty

When a CEO has people who’ve stayed for decades, there’s deep mutual respect there. But it can also become a trap.

The other side of it? They tolerate behavior they shouldn’t because of history.

A superstar who’s been there for fifteen years gets a pass for things that would get someone else fired. The CEO tells themselves, “That’s just how they are.” Or, “They’ve earned the right.”

The rest of the team sees this. And they learn that rules don’t apply equally. That tenure is protection. That power is about relationships, not performance. That’s fertile ground for factions and resentment.

The Painful Truth

Here’s what makes this so difficult.

Every one of these commitments feels like a virtue. Being kind. Being fair. Wanting harmony. Valuing loyalty. Staying above pettiness.

These are good things. They’re probably why people respect this CEO. They’re probably why people have stayed so long.

But taken too far—or left unexamined—they create the conditions for exactly what the CEO hates.

The CEO’s kindness, without clarity and courage, becomes a fertile ground for dysfunction.

Nobody’s being malicious. But the system is producing politics because the leader – without realizing it – has made politics the only viable path.

What Might Be Missing

If I had to name what’s absent, it would be these:

Naming reality.

Sitting the team down and saying, “Here’s what I see happening. The politics. The groupisms. The gossip. It’s not acceptable. And I’m willing to look at how I’ve contributed to it.” Most leaders skip this. They address symptoms. They talk to individuals. They hope things or people will change. It won’t. Someone has to name the thing out loud.

Making hard calls.

Superstars need clarity. They need to know who owns what. Whose strategy wins. Where the boundaries are.

When everything is open for negotiation, people negotiate through power instead of merit. The CEO has to be willing to decide—even when it disappoints someone.

Holding people accountable visibly.

Not in a shaming way. But in a way that signals to the whole team: this behavior has consequences. We don’t do politics here. We don’t tolerate undermining. The founder/CEO has to be willing to say: “This is no longer ok.” or “This can never happen again.”

If accountability only happens in private, the team never sees it. And what the team doesn’t see, the team doesn’t believe.

Having the conversations nobody wants to have.

Bringing two warring leaders into a room and saying, “We’re not leaving until this is resolved.” Letting the discomfort happen instead of smoothing it over. Most kind people avoid this. It feels aggressive. It feels risky. But it’s the only way through.

Powerful leaders raise the tension and let their people grow through the tension. They do not avoid the tension – or defuse it too early.

Letting go of someone they care about.

Sometimes, one person is the source. And the CEO knows it. But they can’t bring themselves to act because of history, loyalty, or genuine affection.

So the whole system stays sick to protect one relationship.

This might be the hardest one of all. And often, it’s the one that would change everything.

The Shift

This isn’t about becoming less kind. The world needs kind leaders.

But kindness without clarity creates confusion. Kindness without courage enables dysfunction. Kindness without accountability becomes complicity.

The shift is learning to be both.

Kind and clear. Kind and direct. Kind and willing to make the hard call.

That’s not a contradiction. That’s integration.

And that’s the leader this team of superstars is waiting for.

They don’t need someone who keeps the peace. They need someone who builds the peace – by being willing to disrupt the false comfort of gossip, politics, and rumors.

That’s when everything changes. What are your competing commitments?

Leave a Reply